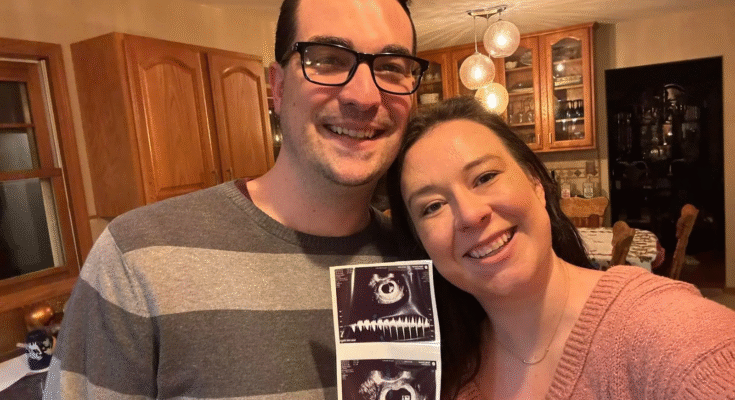

They say that some people smile brightest when they’re breaking. And on the internet, the smiles never fade. Scroll long enough through your feed, and you’ll see them: the perfect couples in front of Cinderella’s Castle, the glittering fireworks above laughing faces, the hashtags that promise magic — #DisneyForever, #HappiestPlaceOnEarth.

But behind some of those smiles lies something far heavier than the mouse ears and fairy dust can hide — a silence so deep it swallows even the sound of joy.

That’s the cruel paradox of the world’s happiest places. They attract dreamers, believers, and people who long for a little more light. And sometimes, those same places become the final destination for those whose light has gone out completely.

It’s a pattern that few want to talk about out loud — a collision of escapism and despair. The theme park, the fan community, the influencer world, the endless smiles — all built to keep the magic alive. But behind the magic, a quiet truth lingers: some people fall in love with happiness because they’ve forgotten how to feel it.

In every fandom, there are those who dedicate their lives to it. They collect, they travel, they post. They become symbols of cheer, human embodiments of fantasy. They know every song, every line, every secret corner of the park. To their online followers, they’re pure joy. To the corporations, they’re dream customers. To themselves, though — they’re sometimes just trying to keep the dream alive long enough to forget what’s missing.

Social media loves them because they’re reliable doses of serotonin. It doesn’t see the bills behind the vacations, the exhaustion behind the smiles, or the loneliness behind the hashtags. Every “like” becomes a validation that maybe, just maybe, the magic still works.

But when that magic runs out, when the last firework fades and the phone battery dies, there’s a silence no camera can fill.

Experts have a name for it now — “fandom fatigue” or “identity over-attachment.” It’s what happens when the thing you love becomes the thing you live for, when your emotional survival depends on an external source of happiness. Whether it’s a franchise, a celebrity, or a community — it offers escape, purpose, belonging. But when life outside that bubble starts to hurt, the bubble becomes a lifeline. And lifelines, when stretched too thin, can snap.

Mental health advocates have been warning about this digital illusion for years. The more we curate our joy online, the more we hide our pain. We’ve built a world where sadness feels like a flaw and struggle feels like a brand mistake. It’s why some of the most seemingly radiant people vanish suddenly, leaving behind stunned followers who can’t understand what they missed.

“I just talked to her yesterday,” one fan might say. “She seemed so happy.”

“She just posted a video!” another comments. “She was singing, she was laughing!”

But happiness online is performance art. The internet doesn’t record what happens after you close the app — when the house is quiet, the messages stop, and the smiles collapse in the dark.

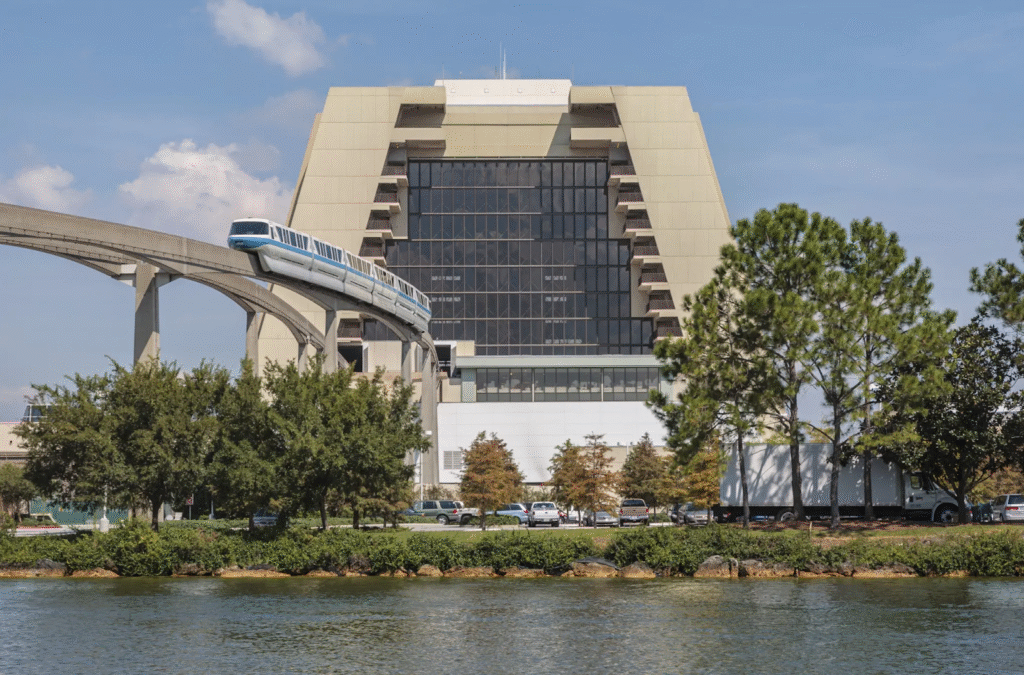

There’s an especially cruel irony when these tragedies unfold in places built for happiness. Theme parks, music festivals, or dream vacations — they’re the places people go to forget the world. They promise safety, escape, and nostalgia. But when someone’s heart is breaking, that kind of beauty can cut both ways.

Because nothing magnifies sadness like being surrounded by joy.

Psychologists say this “contrast effect” — being in a joyful environment while feeling internally shattered — can deepen despair. It’s the emotional equivalent of standing in the middle of fireworks with your soul in total darkness.

“People often go to happy places to fix sad feelings,” says Dr. Ellen Ward, a clinical psychologist specializing in trauma and social media behavior. “But when the joy around them doesn’t fix the pain inside them, it can make them feel even more alone — like there’s something fundamentally broken about them.”

The danger, Ward says, is how silent that suffering can be. “No one expects someone smiling at a theme park to be suicidal,” she explains. “The setting itself masks distress. It’s the perfect camouflage.”

And when those settings are wrapped in nostalgia — like Disney, where millions associate every sound and color with childhood innocence — the psychological dissonance can be overwhelming. “It’s the safest, happiest imagery imaginable,” Ward says. “If someone feels darkness there, they may interpret it as proof that the darkness is inside them — not the world.”

In recent years, rescue workers, hotel staff, and security teams near major resorts have quietly admitted a heartbreaking trend: a growing number of self-harm incidents in or near vacation properties. These are not statistics anyone wants to advertise. “It’s bad for business” is the blunt way one staffer put it. But the truth is, emotional crises don’t pause for family vacations.

In fact, for some, the trip itself becomes a final attempt at reclaiming happiness — a symbolic return to where they once felt safe. “It’s not that they want to die there,” said another counselor. “It’s that they want to feel there one last time.”

But when the fantasy doesn’t deliver salvation, despair sets in fast.

And then the headlines come. The public mourns, the internet speculates, the corporations issue statements about “thoughts and prayers.” For a few days, the tragedy dominates timelines — the contrast between “The Happiest Place on Earth” and the cruelty of reality proving too sensational to resist.

But soon, attention fades. The park gates reopen, the music plays again, and the cycle continues.

Because in modern culture, sadness is a scandal — and scandals must move on.

There’s another layer to this tragedy that feels uniquely 21st-century: the obsession with public image.

Online fan communities can be incredibly loving — but they can also be suffocating. To remain adored, you must remain cheerful. To remain relevant, you must keep posting. Followers come for happiness, not heaviness. That pressure to stay “on” is its own quiet kind of torment.

Mental health activists have compared influencer culture to emotional theater — one that rewards authenticity only when it looks good. Vulnerability sells if it’s pretty, pain is accepted if it’s poetic, and sadness is tolerated only if it fits the narrative arc of redemption. But real suffering — the raw, messy, silent kind — doesn’t trend.

That’s why so many cries for help never make it past the drafts folder.

And yet, when tragedy strikes, everyone asks the same question: “Why didn’t they tell someone?”

Maybe they did. Maybe they just didn’t use the words you wanted to hear.

There’s a hard truth that no one wants to admit: we are terrible at listening to sadness. We change the subject, offer clichés, or swipe away. We don’t want to feel helpless, so we choose disbelief. “You have so much to live for,” we say — not realizing that the person already knows that. That’s what makes it hurt so much.

Society still treats mental illness like a moral contradiction: if you’re loved, you can’t be lonely. If you’re successful, you can’t be suffering. If you’re standing in the happiest place on Earth, you can’t be breaking inside.

But you can.

And the more we pretend that’s impossible, the more people we lose in silence.

This isn’t a story about any one person — it’s about all of us. It’s about the parts of society that worship happiness so blindly that we forget sadness is human. It’s about how our digital world rewards pretending, punishes honesty, and commodifies emotion.

It’s about how, in chasing perfection, we’ve made it impossible for people to show pain.

Every time a tragedy like this happens, the pattern repeats: online memorials, disbelief, blame, then silence. The parks reopen. The comments fade. But somewhere, another person scrolls through smiling faces, feeling that same quiet alienation — wondering why they can’t feel what everyone else seems to.

That’s the invisible epidemic of this generation.

We’ve built the most connected world in history — and yet millions feel completely alone inside it.

If there’s a way forward, it begins with empathy — real empathy, not hashtags or performative posts. It means creating space for discomfort, for honesty, for people to say “I’m not okay” without fear of ruining the mood. It means letting joy and pain coexist without shame.

It means teaching people that the happiest places on Earth are still part of the real world — and real worlds contain heartbreak too.

Imagine if our culture made room for both magic and melancholy — if we didn’t demand constant positivity from those who make us smile. Maybe then, when someone’s light begins to dim, they’d feel safe enough to say something before it goes out completely.

Until then, we’ll keep mistaking smiles for strength, posts for peace, and fandom for family.

But somewhere out there, someone’s standing under the fireworks, wishing the magic could reach them — and realizing it can’t.

Maybe the most important truth of all is this: no one is immune to despair. Not the fans, not the dreamers, not the ones who make us believe in magic. Sometimes the people who give the most light are the ones who need it back the most.

And maybe, just maybe, the real miracle isn’t the park or the castle or the fairytale. It’s the moment when someone looks past the smile, hears the silence, and decides to reach out.

Because joy can’t save us from pain — but kindness just might.

🕊 If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, you are not alone.

In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

If outside the U.S., you can find international helplines here: [findahelpline.com], which connects you to free, confidential support in your country.