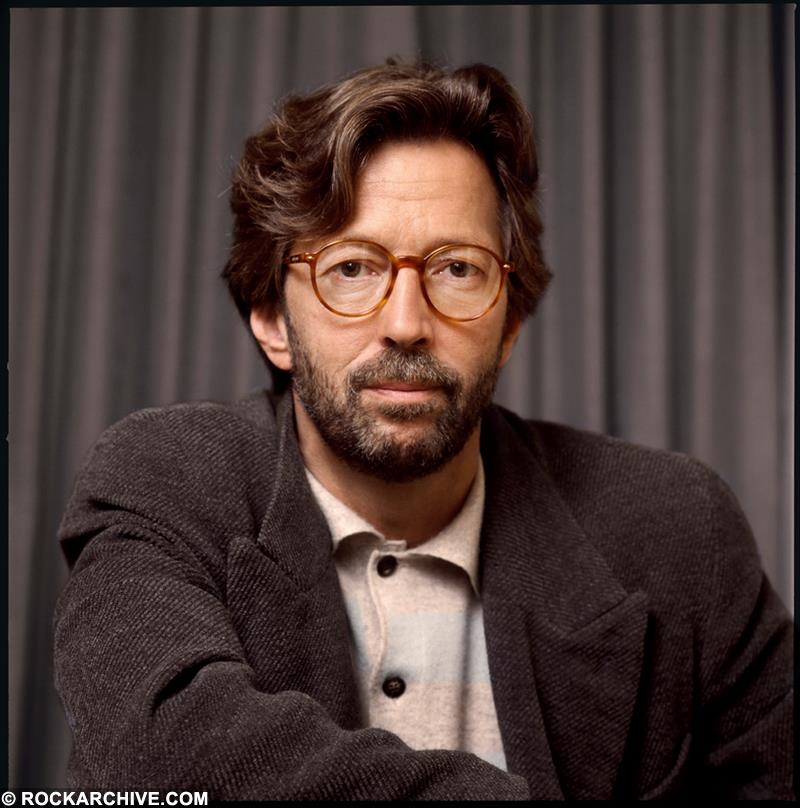

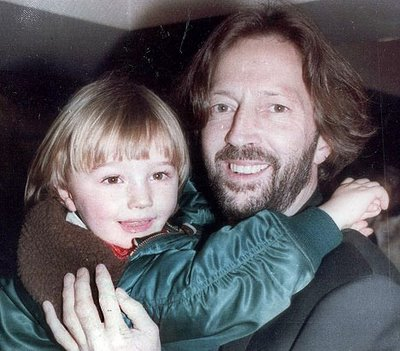

I used to believe there was nothing in this world I couldn’t face — not after the years of addiction, heartbreak, and fame that could lift you to heaven just to throw you back down. I survived all of that. But nothing prepared me for the call I received that morning in 1991. I walked to that building in New York thinking I was about to start a simple day with my little boy. Instead, I walked into a nightmare I still replay when the world falls quiet.

When Conor died, a part of me died too — a part I’ll never get back. People talk about grief like it’s a storm, but storms pass. This didn’t. It settled in my bones. I was a man with a guitar and no language for the pain I was holding. Fame means nothing when you are standing in front of a hospital door praying God made a mistake. No applause can drown out silence that heavy.

I isolated myself — not because I wanted to disappear from the world, but because I didn’t know how to exist in it anymore. There were days I couldn’t speak, nights where I wished I could trade every song I’d ever played for just one more morning with my son. I had been reckless in my life, careless with myself. But never did I think the world would take him, not me. That’s the kind of thought that keeps you awake for years.

I carry regrets. Regrets that I wasn’t there every single day. Regrets that life and work pulled me away. Regrets that I believed I had time — because every parent thinks they have time. You imagine future birthdays, laughter, little hands growing bigger. You never imagine a window. You never imagine a fall. I would have given anything — anything — to hold him closer. That’s the truth I live with.

Music became my only way forward. I didn’t write “Tears in Heaven” as a song — I wrote it as a question to the universe. A conversation with a child I could no longer speak to. Every chord felt like breaking a rib just to breathe. But when I played it, I could feel him near — not gone, just somewhere I couldn’t reach yet. That song didn’t save me, but it kept me from drowning.

The world heard a ballad. I heard a prayer. People say it healed them, that they found comfort in it. And I am grateful. But it wasn’t written for comfort — it was written from a wound so deep I wasn’t sure I would survive it. When the letters came, parents sharing their grief with mine, I realized something: pain doesn’t isolate — it connects. Tragedy pulls souls together in ways joy never can.

There came a point when I stopped performing the song. Not because I stopped loving my son, but because grief is a visitor, not a home. I had lived with a hole in my chest long enough. I wanted to remember Conor for his laughter, not his absence. Healing didn’t mean forgetting — it meant learning to live with memory instead of sorrow.

I still think about him every day. There are moments — a quiet morning, a child laughing, sunlight through a window — when I feel him. And in those moments, I don’t feel broken. I feel like a father again, just for a second. That’s enough.

If I could speak to him now, I wouldn’t sing. I’d just say, “I’m sorry. I love you. And I’m still trying.” And I hope, wherever he is, he knows.

Because heaven isn’t far away. Pain just makes it feel that way.