The savanna breathes in gold and amber, endless and untamed, as Meryl Streep’s Karen Blixen steps into it like a woman being reborn. Her Danish precision softens into wonder beneath the African sun, where porcelain teacups are replaced by red dust and the steady rhythm of cicadas.

She leaves behind Copenhagen’s civility for the chaos and beauty of Kenya, where dreams grow like wild grass and failure lurks in the soil. With her coffee plantation as both refuge and battlefield, Blixen learns that the land is alive — a living god that offers everything and takes it all back.

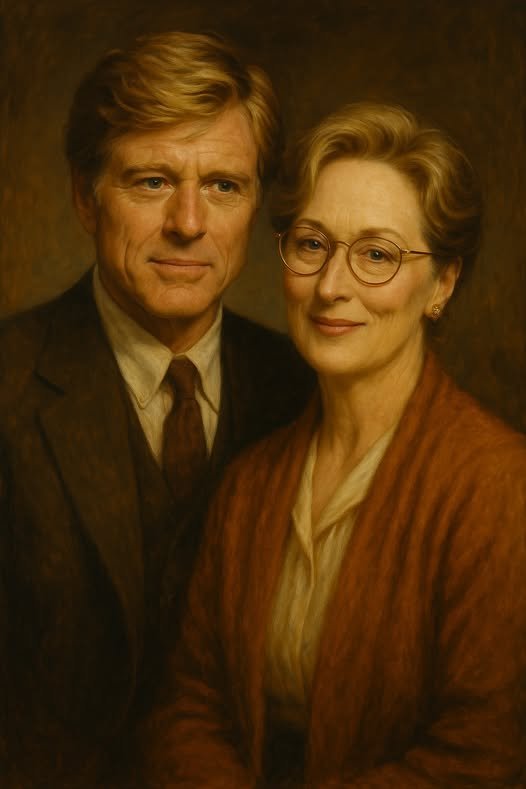

Robert Redford’s Denys Finch Hatton enters like a breeze from the highlands — sun-bleached hair, disarming grin, and eyes that hold the horizon. He is freedom personified, a man who belongs to no one, whose love feels like flight. Together, they dance between independence and intimacy, never quite meeting in the middle.

Their romance unfolds not in whispers, but in silence — the kind that lives between the rustle of grass and the cry of distant lions. Redford’s Denys refuses to be tamed, and Streep’s Karen, for all her strength, cannot hold him without clipping his wings.

Sydney Pollack directs like a painter chasing light. Every frame glows — dawn spilling across the Ngong Hills, the sky igniting over endless plains, and the slow, golden fade of twilight. Africa isn’t just a backdrop; it is the third lover in their story.

John Barry’s score swells with heartbreak, its strings carrying both the ache of loss and the beauty of surrender. It’s a symphony of longing — one that lingers long after the screen fades to black, echoing like the hum of wind through acacia trees.

Streep gives one of her most restrained and luminous performances — her Karen is fragile yet defiant, wounded yet unbroken. When she reads her stories to Kikuyu children or stands alone on the empty farm, there is poetry in her solitude.

Redford plays Denys with quiet electricity — a man of adventure and contradictions, torn between love and the wild. His final flight feels both inevitable and unbearable, a vanishing act written in smoke and memory.

When the plane disappears over the horizon, Karen’s voice carries what remains: the memory of a man who refused to stay, and a land that never lets go. Love, here, is not about possession — it’s about the courage to let something beautiful remain free.

Out of Africa won seven Oscars, including Best Picture, Director, and Cinematography, but its truest legacy lies in the ache it leaves behind. It’s a film that doesn’t age; it matures like wine — deeper, richer, and more haunting with time.

Decades later, as that sweeping score rises once more, we remember them — Streep and Redford, Blixen and Finch Hatton — suspended forever in the amber light of a land that still whispers their names.