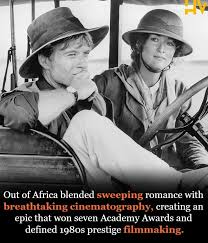

The hair-washing scene in Out of Africa remains one of cinema’s most intimate moments, a fusion of tenderness, poetry, and unspoken longing. Robert Redford as Denys Finch Hatton and Meryl Streep as Karen Blixen transform a simple act by the river into a quiet declaration of trust. The moment is so iconic that it has outlived even the film itself, becoming a symbol of the wilderness romance at the center of Sydney Pollack’s 1985 epic.

As Denys gently pours water over Karen’s hair, he recites lines from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The choice is deliberate. The poem — a meditation on fate, nature, and the cost of human choices — mirrors the emotional landscape of both characters. It is a haunting reminder that their love exists within the vastness of the African plains, fragile and transient.

Redford delivers the verse with quiet restraint, giving it the weight of memory rather than performance. His voice blends with the sound of the river and the sweep of the wind, creating a scene that feels almost suspended in time. The intimacy is not physical alone; it is intellectual, spiritual, and deeply emotional. It shows how Denys moves in Karen’s world with poetry rather than promise.

The line he quotes — “He prayeth best, who loveth best / All things both great and small” — is now inseparable from the film. It speaks to Denys’s reverence for the wild, his belief in freedom, and his refusal to own or be owned. That philosophy of love, unbounded and untamed, is what draws Karen to him and ultimately breaks her heart.

What many viewers never realize is that these very words are inscribed on the real gravestone of Denys Finch Hatton in Kenya. The filmmakers did not invent the reference; they honored a piece of history. Finch Hatton, a British aristocrat and aviator, died in a plane crash in 1931. His gravestone bears the same Coleridge line — a tribute to the man who lived closest to the land he loved.

The inscription adds a layer of poignancy to the film. When Redford recites the verse, he is not only playing a character; he is echoing the legacy of the real Denys. It binds the world of Isak Dinesen’s memoir, the film’s dramatization, and the historical person in one quiet moment by the river. Few scenes in cinema blend fiction and reality so gracefully.

Meryl Streep’s performance heightens the emotional resonance. Her face — eyes closed, breath steady, surrendering not in weakness but in trust — carries a kind of vulnerable strength. The scene becomes a portrait of a woman learning to love without control, the way Africa teaches her to live. Streep does not need dialogue; the landscape and her expression speak for her.

Director Sydney Pollack understood the power of silence, and this scene demonstrates his mastery. Nothing flashy happens. No sweeping music, no dramatic declarations. Just two people, water, and a poem. The simplicity is its brilliance. It reminds audiences that intimacy can be cinematic without spectacle — a truth often lost in modern filmmaking.

The hair-washing sequence also reflects the film’s central theme: that some loves are shaped as much by freedom as by connection. Karen loved Denys precisely because he belonged to no one, not even himself. The poem he quotes reinforces that philosophy — to love best means to love without possessing. It is a lesson that shapes Karen long after his death.

Even now, decades after the film’s release, the scene continues to be studied and admired for its craft, symbolism, and emotional precision. It endures because it feels real — a rare fusion of history, literature, and performance. It is one of the moments that elevates Out of Africa from a love story into a meditation on what it means to love at all.

For those interested in the historical context, here is a reference to the real Denys Finch Hatton and the