The 1976 National Geographic assignment that sent Robert Redford down the legendary Outlaw Trail became one of the most iconic intersections of Hollywood charisma and Western history. What began as a magazine cover story soon expanded into a book and later a television documentary, each exploring the rugged terrain and mythic landscape that once sheltered fugitives of the American West. Redford, already synonymous with frontier roles, dove into the project with unusual personal passion.

In retracing the route once used by Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and countless lesser-known desperadoes, Redford wasn’t simply reenacting history—he was interrogating the cultural ideas that shaped the outlaw myth. The trail, stretching from Montana through Wyoming and Utah before slipping into Mexico, offered him a narrative spine to examine the American fascination with rebellion, escape, and rugged individualism. National Geographic’s editorial vision gave the story a documentary realism rarely matched in celebrity-led features.

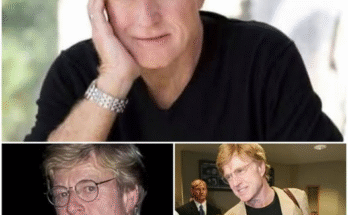

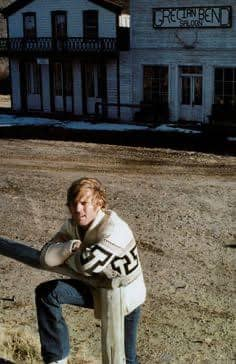

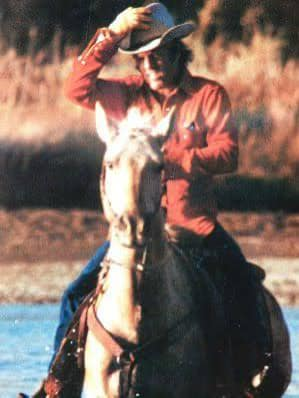

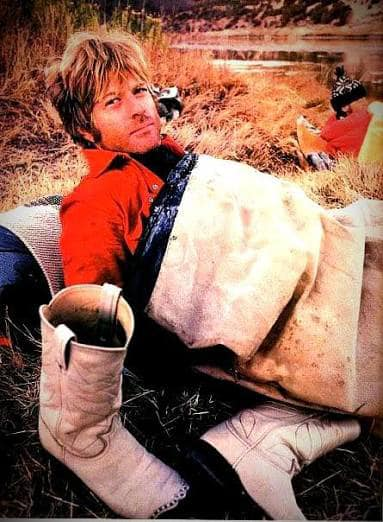

Photographer Johnathan Blair’s images played a crucial role in making the project unforgettable. His photographs captured Redford in stark, sweeping landscapes—riding alone across desert valleys, studying eroded hideouts, and standing before canyon walls that had not changed since the days of the early bandits. Blair’s visual storytelling bridged past and present, grounding Hollywood glamour in the rawness of real history. For many readers, the images became defining symbols of 1970s Western nostalgia.

Redford’s journey also highlighted how geography shaped the lives of the outlaws. The trail was not a single road but a network of obscure hideouts, canyon passes, and remote ranches used to evade lawmen. Each stop along the route revealed how deeply intertwined the fugitives’ survival was with the land itself. Redford’s reflections in the piece underscore his belief that the West’s physical harshness forged a certain philosophy—half freedom, half desperation.

By the time the November 1976 issue of National Geographic was released, the story had become more than a travelogue; it became a meditation on the mythology of the American frontier. Redford’s narrative voice, both introspective and historically grounded, invited readers to reconsider the outlaw not simply as a romantic figure but as a product of social, political, and geographic forces. The magazine issue sold widely, reinforcing Redford’s association with authentic Western storytelling.

The success of the article paved the way for the book adaptation, which expanded the research and included additional photographs from Blair. The book offered a deeper dive into the lesser-known figures who lived along the trail, from ranchers who offered shelter to Native communities whose lands the outlaws traversed. Redford’s commentary remained central, balancing personal observation with documentary-style reporting. For many fans, the book remains one of his most thoughtful works.

Television audiences later encountered the story through the documentary version, which aired to strong viewership. The film followed Redford as he rode through the same dusty corridors once used by the fugitives, using on-location interviews and historical footage to bring the Outlaw Trail to life. His calm, reflective narration gave the documentary an emotional richness, emphasizing how legends endure long after the real men have vanished. Critics praised it for mixing scholarship with cinematic beauty.

One of the documentary’s most compelling themes is the tension between myth and truth. Redford repeatedly asks what the outlaw figure meant to earlier generations and what it symbolizes today. The program challenges viewers to understand the outlaw not merely as a hero or villain but as a product of frontier survival, economic hardship, and cultural imagination. In doing so, it asks broader questions about why societies elevate certain figures into legend.

The project also arrived during a cultural moment when Americans were re-evaluating national identity. In the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate, the Western landscape—timeless, rugged, and uncorrupted—offered symbolic escape. Redford’s journey along the Outlaw Trail tapped into this longing for authenticity. His portrayal of the West as a place of memory and introspection resonated deeply. Readers and viewers found in the story both nostalgia and a sense of renewal.

Though nearly five decades have passed, “The Outlaw Trail: A Journey Through Time” remains one of Redford’s most defining nonfiction ventures. It stands alongside his film work as evidence of his commitment to preserving Western history and interrogating American mythmaking. The trail itself has evolved into a cultural landmark, with modern travelers retracing segments inspired by the 1976 feature. Redford’s involvement helped ensure its place in public imagination.

Today, the project is remembered not only for its historical value but for its artistic collaboration. The partnership between Redford and Blair produced a body of work that blended photography, journalism, and personal exploration. The magazine, book, and documentary continue to be cited as references for scholars of Western culture. For fans of Redford, the project reflects his lifelong dedication to storytelling that honors both landscape and legacy.